The power of a magnet—its ability to attract or repel with force—is not a matter of chance. It is the result of careful material selection, precise manufacturing, and specific design choices. Understanding what determines magnetic strength is crucial for engineers designing everything from micro-motors to large-scale magnetic separators.

A magnet's strength is primarily defined by four key factors: Material Composition, Magnetization Process, Physical Shape, and Temperature. Let's explore how each element contributes to the overall power of a magnet.

1. Material Composition: The Intrinsic Power

The single most important factor determining a magnet's potential strength is the material it is made from. This is quantified by a material property called the Maximum Energy Product ((BH)max), which represents the maximum energy density the magnet can sustain.

Rare-Earth Dominance: Today, the strongest magnets are made from rare-earth alloys, specifically Neodymium Iron Boron (NdFeB). These materials possess a unique crystal structure that forces the atomic magnetic moments to align strongly and resist external fields, resulting in a (BH)max far superior to traditional ceramics or Alnico.

Coercivity (Hc): This is the measure of a magnet's resistance to being demagnetized. A material with high coercivity, like NdFeB or Samarium Cobalt (SmCo), will maintain its magnetic field strength even when exposed to opposing fields or elevated temperatures.

Residual Induction (Br): This represents the magnetic flux density remaining in the material after the external magnetizing field has been removed. Higher Br generally means a stronger surface field and is critical for generating powerful attraction.

2. The Magnetization Process: Alignment is Key

Even the best material is just a block of metal until it is magnetized. The manufacturing step where the material is exposed to an intense magnetic field is vital.

Orientation: During the manufacturing process (often sintering), the magnetic particles within the material are aligned in a preferred direction before they are permanently fused. This is called creating an anisotropic magnet, and it yields a significantly stronger field in the direction of orientation than an isotropic magnet (which can be magnetized in any direction).

Saturation: To achieve maximum strength, the material must be exposed to a magnetizing field strong enough to fully saturate the magnet. This means ensuring that virtually all the microscopic magnetic domains within the material are permanently aligned with the intended magnetic direction.

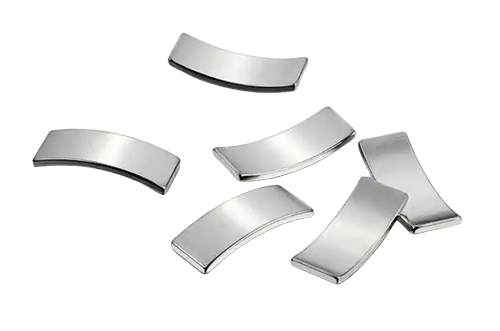

3. Physical Shape and Size: Design Matters

For a finished magnet, the way it is shaped and sized directly impacts the strength of the magnetic field outside the material.

Size (Volume): Generally, a larger magnet of the same material will be stronger because it contains more magnetic domains contributing to the overall field.

Thickness (in the direction of magnetization): The length of the magnet along the direction of its poles (the magnetic axis) is crucial for generating a strong external field. A thicker magnet is better able to resist self-demagnetization and project a field over a longer distance.

Pole Area: The area of the surface facing the object (the pole face) affects the pull force or surface field strength. A larger pole area will often have a higher pull force when in direct contact with a ferromagnetic surface.

4. Environmental Factors: The Influence of Heat

Temperature is the ultimate enemy of a permanent magnet. Exposure to heat can drastically reduce strength.

Curie Temperature (TC): This is the critical temperature at which a magnet loses all of its ferromagnetic properties and becomes paramagnetic.

Maximum Operating Temperature: Even below the Curie temperature, most magnets experience a reversible loss of strength as the temperature rises. For example, a Neodymium magnet operating above 80°C will be weaker than the same magnet at room temperature. For maximum strength retention, the magnet must be kept well below its maximum operating temperature.

In Summary

To create the strongest possible magnet, manufacturers must:

1. Choose a High-Energy Material (e.g., Neodymium) to maximize the intrinsic (BH)max.

2. Ensure Proper Anisotropic Orientation and Saturation during manufacturing.

3. Optimize the Geometry by selecting the right volume and pole dimensions for the application.

4. Control the Operating Temperature to prevent thermal demagnetization.

By mastering these four areas, the latent power within the raw magnetic materials is unlocked, resulting in the powerful components that drive modern innovation.

We will contact you within 24 hours. ( WhatsApp/facebook:+86 15957855637)